Notes: The following information is intended for health care professionals. Always read the label and follow the instructions for use. For information on the efficacy and the side effects, refer to the instructions for use. Products are only for sale to health professionals.

Placement of the acetabular component is often reported as two angles, inclination and anteversion. This post explains how these angles are calculated and whether these angles matter.

Hip Replacement Components

During total hip replacement, an acetabular component (or cup) is inserted into the pelvis. The head of the femoral component fits into the acetabular component, replacing the hip joint. The stem of the femoral component is inserted into the femur, attaching the leg to the hip.

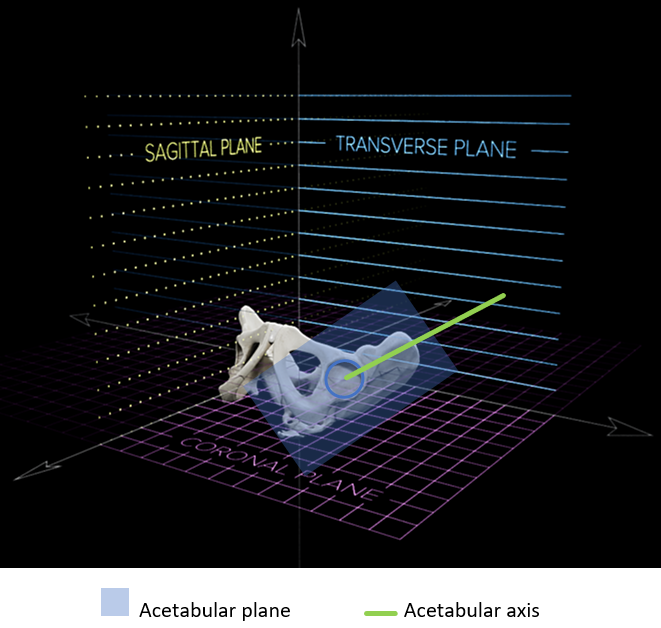

Acetabular Axis

When we measure acetabular cup inclination and anteversion angles, we measure the orientation of the acetabular axis. The acetabular axis is a line through the centre of the acetabular cup and orthogonal to the acetabular plane1, i.e. the acetabular axis is at 90° to the acetabular plane in every direction. The acetabular plane is the flat surface which lies on the rim of the acetabular cup1.

Reference Plane

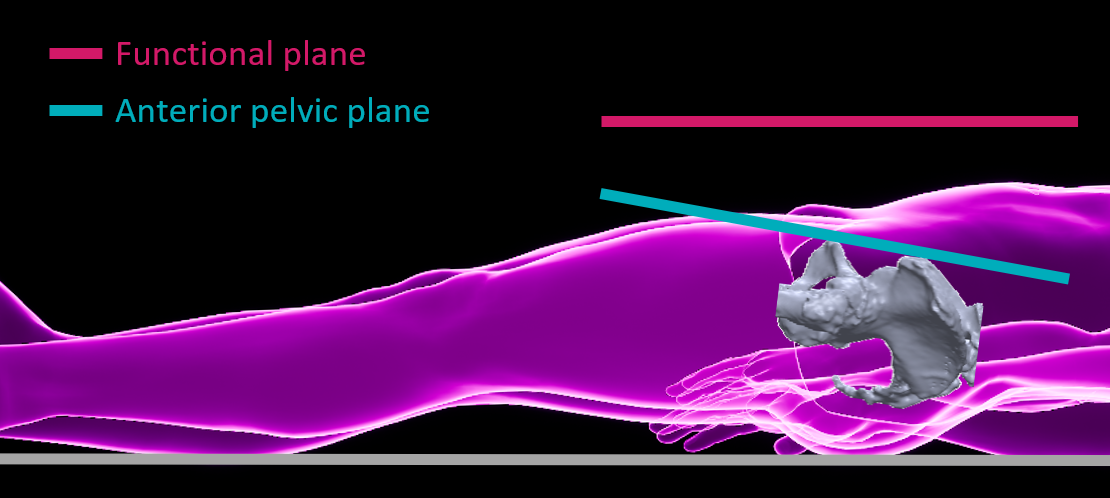

The inclination and anteversion angles of the acetabular axis (and therefore, the acetabular cup) are measured relative to a reference plane. There are multiple options for reference planes. Different reference planes lead to different measurements, so it is important to know what reference plane is being used for a reported angle.

Two potential reference planes are shown below for the supine position. The anterior pelvic plane is an anatomic reference plane which is defined by the anterosuperior iliac spines (ASISs) and the pubic tubercles2. When the patient is supine, a functional coronal reference plane is one that is parallel to the operating table plane. When the patient stands, the functional coronal plane is vertical. The influence of reference planes on the accuracy of navigation is explored here.

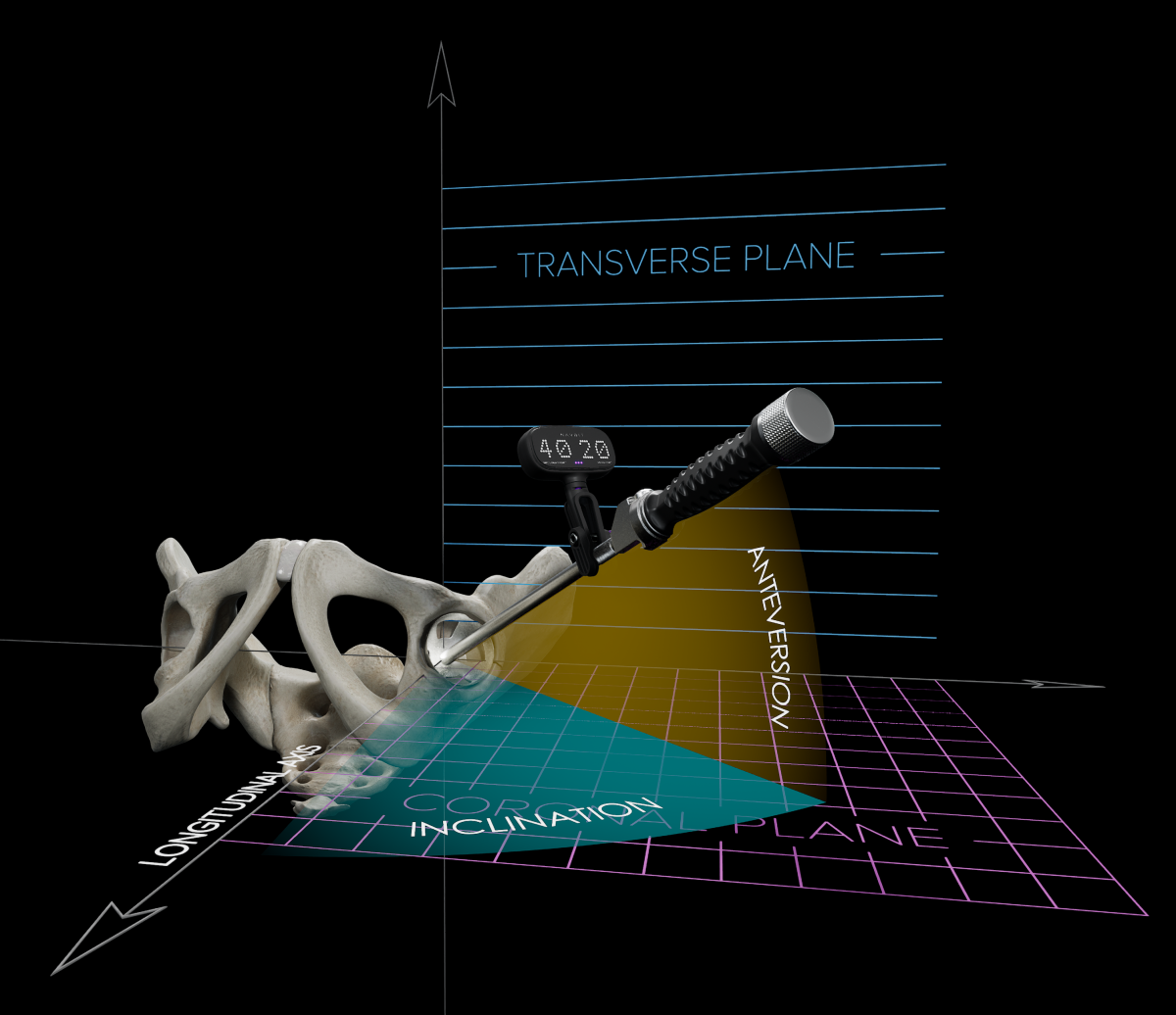

Acetabular Inclination and Anteversion

The definitions provided by Murray3 remain influential for measuring the inclination and anteversion angles of the acetabular cup. Murray defined three types of measures of inclination and anteversion: radiographic, operative, and anatomical. As we mentioned above, these angles are measured relative to a reference plane. Therefore, the inclination and anteversion angles depend on (1) the type of measure (radiographic, operative, or anatomical), and (2) the reference plane being used (e.g. anterior pelvic plane, functional plane).

Radiographic Inclination and Anteversion

The radiographic measures are often reported for acetabular cup inclination and anteversion, such as by the Navbit Sprint System. Using a functional coronal reference plane as an example, radiographic inclination and anteversion are illustrated below. Radiographic anteversion is the angle between the acetabular axis and the reference plane3. Radiographic inclination is the angle between the longitudinal axis of the body and the acetabular axis when it is projected onto the reference plane3.

Do Acetabular Inclination and Anteversion Matter?

A broader question is whether acetabular cup position matters. Research suggests that it does.

In a retrospective review of patients after surgery4, for the 51.3% of revision THAs which were deemed avoidable, the primary reason for revision was suboptimal positioning of the acetabular cup, accounting for 48.3%.

In an Australian joint registry study5, using navigation to improve acetabular component placement was associated with a significantly lower cumulative risk of dislocation at 10 years (0.4%) compared with non-navigated surgeries (0.8%).

In a UK joint registry study6, 10 years after surgery, patients had a lower risk of revision if navigation was used (1.06%) than if navigation was not used (3.88%).

Based on these studies, improving the position of the acetabular cup is associated with lower rates of dislocation and revision surgery.

References

- Harrison CL, Thomson AI, Cutts S, et al. Research Synthesis of Recommended Acetabular Cup Orientations for Total Hip Arthroplasty. The Journal of Arthroplasty 2014;29(2):377-82. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.06.026

- Bhaskar D, Rajpura A, Board T. Current Concepts in Acetabular Positioning in Total Hip Arthroplasty. Indian journal of orthopaedics 2017;51(4):386-96. doi: 10.4103/ortho.IJOrtho_144_17

- Murray DW. The definition and measurement of acetabular orientation. Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery 1993;75(2):228-32. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.75b2.8444942 [published Online First: 1993/03/01]

- Novikov D, Mercuri JJ, Schwarzkopf R, et al. Can some early revision total hip arthroplasties be avoided? The Bone & Joint Journal 2019;101-B(6_Supple_B):97-103. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.101B6.BJJ-2018-1448.R1

- Agarwal S, Eckhard L, Walter WL, et al. The Use of Computer Navigation in Total Hip Arthroplasty Is Associated with a Reduced Rate of Revision for Dislocation: A Study of 6,912 Navigated THA Procedures from the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. JBJS 2021;103(17):10.2106/JBJS.20.00950. doi: 10.2106/jbjs.20.00950

- Davis ET, McKinney KD, Kamali A, et al. Reduced Risk of Revision with Computer-Guided Versus Non-Computer-Guided THA: An Analysis of Manufacturer-Specific Data from the National Joint Registry of England, Wales, Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man. JBJS Open Access 2021;6(3)