Notes: The following information is intended for health care professionals. Always read the label and follow the instructions for use. For information on the efficacy and the side effects, refer to the instructions for use. Products are only for sale to health professionals.

Previously, we’ve talked about hip dislocation and the possibility that dislocation rates are underestimated.

Here, we consider the impact of dislocations.

Dislocations Cause Revision Surgery

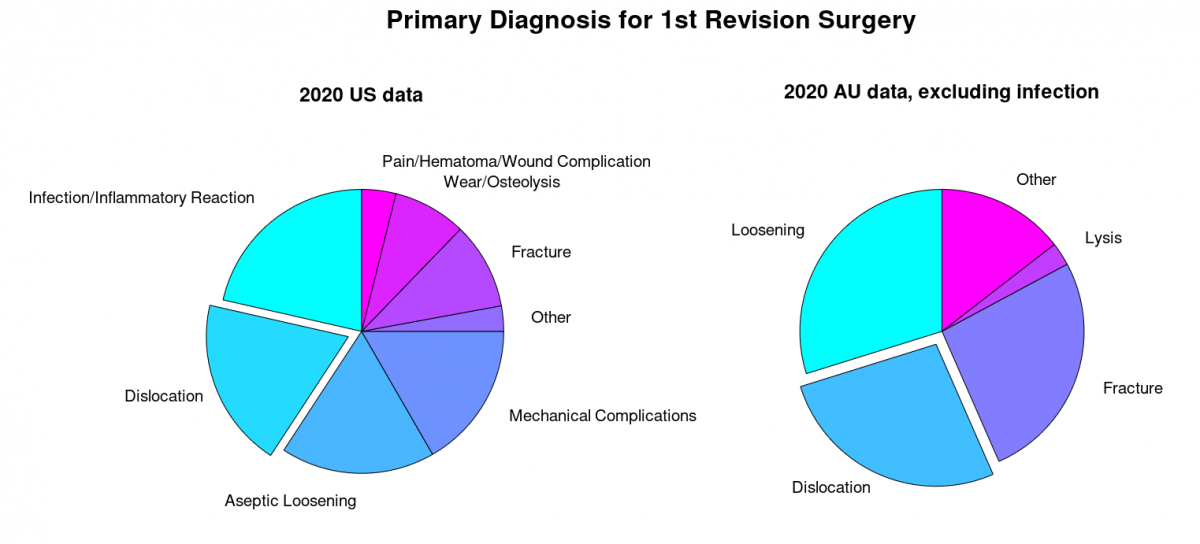

Dislocation is a primary cause of revision and re-revision surgery. In the US from 2012 to 2019, instability (which includes dislocation) accounted for 17.4% of 49,024 revision hip arthroplasties and was the second most prevalent reason for revision1. In Australia, from 1999 to 2019, dislocation of the prosthesis was the second most common reason for the first revision surgery (26.8%)2 and the most common reason for a second revision surgery (33.7%)2. These findings are consistent with a study in the US that analysed records from 2009 to 2013 in the National Inpatient Sample database. In this study, the most common cause of revision THA was dislocation (17.3%), with mechanical loosening a close second (16.8%)3.

Note: Data are from Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry (AOANJRR) 2 and American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 1.

Dislocation is Associated with Poorer Clinical Outcomes

The clinical outcomes for patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty (THA) are affected by dislocations. In the US, based on the Hip disability and Osteoeoarthritis Outcome Score (HOOS), 92.5% of patients had a meaningful improvement in outcomes after elective THA1. With dislocation, however, the prognosis was not as positive, with reduced quality of life, mental health, and survivorship. One contributor to poor outcomes is the tendency for dislocation to be recurrent. For example, in Denmark, 41.6% of patients with dislocation experienced more than 2 dislocations in the 2 years post-surgery4. The effect of dislocations on patient well-being were seen in a Swedish study: compared with patients without dislocation, patients with dislocation experienced a significant reduction in quality of life at 4 months, and this reduced quality of life persisted to 12 months for patients with recurrent dislocations5. The reduction in quality of life was related to impaired self-care and normal activities, as well as an increase in anxiety and depression. Dislocation also affects mortality rates. In Australian data, revision due to dislocation was associated with reduced survivorship2. These findings highlight the seriousness of dislocation for patient well-being.

Dislocation also exposes patients to the risk and burden of additional surgery. This revision surgery tends to be soon after the original surgery. For example, in Australia, for revision surgeries due to dislocation, the median time from the primary surgery to revision was 0.8 years (IQR 0.1 – 3.8)2. Similarly, in a nationwide review of Danish THA data, the mean time to revision was 102 days, with 75% within 3 months of the original surgery4. In addition, for dislocation, revision surgery leads to an increased risk of re-revision surgery. For example, in Australia, dislocation is the most likely reason for a second revision surgery after a first revision for dislocation2.

Image by 👀 Mabel Amber, who will one day from Pixabay

Summary

The effect of dislocation on patient outcomes and the potential underreporting of dislocation rates highlight the problem of dislocation. Dislocations tend to be recurrent. Dislocations are associated with reduced quality of life, mental health, and survivorship, especially if recurring. In treating dislocation, revision surgery is often recurrent and exposes patients to the risk and burden of further surgery soon after the original surgery. Such revision surgery also adds cost and demand to healthcare systems.

References

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. The Seventh Annual Report of the AJRR on Hip and Knee Arthroplasty, 2020.

- Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry (AOANJRR). Hip, Knee & Shoulder Arthroplasty: 2020 Annual Report, 2020.

- Gwam CU, Mistry JB, Mohamed NS, et al. Current Epidemiology of Revision Total Hip Arthroplasty in the United States: National Inpatient Sample 2009 to 2013. J Arthroplasty 2017;32(7):2088-92. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.02.046 [published Online First: 2017/03/25]

- Hermansen LL, Viberg B, Hansen L, et al. “True” Cumulative Incidence of and Risk Factors for Hip Dislocation within 2 Years After Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty Due to Osteoarthritis: A Nationwide Population-Based Study from the Danish Hip Arthroplasty Register. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2021;103(4):295-302. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.19.01352

- Enocson A, Pettersson H, Ponzer S, et al. Quality of life after dislocation of hip arthroplasty: a prospective cohort study on 319 patients with femoral neck fractures with a one-year follow-up. Quality of Life Research 2009;18(9):1177-84. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9531-x